Inspector Richard Queen wanted to know the identity of the

murdered man. How could he solve a murder mystery without knowing who was murdered? The

body was found in a private room of the Hotel Chancellor; no one connected with the

investigation had ever seen the man before. His name, where he came from, why he was

there, remain a mystery to the end. Yet all who were enmeshed in the web of the tragedy

found their lives changed by the death of the nameless nobody. A puzzling publishing murder attracts the eye of Ellery Queen. Mandarin Press is a premier publishing house for foreign literature, but to those at the top of this enterprise, there is little more beautiful than a rare stamp. As Donald Kirk, publisher and philatelist, prepares his office for a banquet, an unfamiliar man comes to call. No one recognizes him, but Kirk’s staff is used to strange characters visiting their boss, so Kirk’s secretary asks him to wait in the anteroom. Within an hour the mysterious visitor is dead on the floor, head bashed in with a fireplace poker, and everything in the anteroom has been quite literally turned upside down. The rug is backwards; the furniture is backwards; even the dead man’s clothes have been put on front-to-back. As debonair detective Ellery Queen pries into the secrets of Mandarin Press, every clue he finds is topsy-turvy. The great sleuth must tread lightly, for walking backwards is a surefire way to step off a cliff. |

| "Without doubt the best of the Queen stories." -- New York Times |

|

|

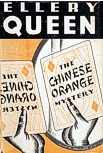

Above: The first books

published sometimes had identical front covers. The spine of the books/dust

cover only differ in the publisher's logo. Top row left to right: Both dust

cover and hard cover for Stokes, dust and hard cover for Grosset &

Dunlap. Bottom row left to right: cover International Readers League, dust cover for Triangle Books followed by three variations for the hard cover (Click on the covers to see the differences) * |

|

The Nassau Daily Review (Long Island),

"Pens and Margins" by Frank A. Culver -

July 10. 1934 "The perennial summer crop of murder-mystery novels proves itself to be in something of a hey-day with the appearance of the titles mentioned above. The Queen opus may be recommended as a puzzler to even the most seasoned readers of detective stories or experts in the deductive art of ratiocination. ... I may say here that I, by no means the most avid follower of mystery tales in this world, was sufficiently diverted to spend a good hour with this book. ... Here the author has gathered all the tricks and properties of the detective story proper, as well as some which must be new to the trade. There is, of course, the inevitable murder. But this is a unique thing in the way of detective story murders. The victim remains unidentified until the very last minute, so to speak; and since the solution of the plot deepens and the mystery thickens continuously up until the last half of the last chapter. I must admit that the solution of the mystery, once it is read, is a bit disappointing. At least, it seemed that way to me. I am a bit wary of detective stories, though, for that very reason. The endings, usually, make me feel as if I had been tricked. Such is the ending of "The Chinese Orange Mystery." The manipulations of Detective Queen seem Just a little reminiscent of those impossible and ridiculously intricate machines that Rube Goldberg invents in his cartoons. But then, after all, I know the solution of the mystery now; and you, my dear readers, do not. And if you submit yourselves to Mr. Queen's compelling enigma, I'll wager that you will be loath to quit the book until the solution, intricate as it is, is yours. That's the worth and the charm of detective stories, until you know what the solution is, it has a charm so wholly magnetic that the complication of incidents possesses itself of your whole consciousness. Suffice it to say that there are many plots and cross plots in this book ... and that before he has solved the mystery itself, the author has also solved several ghastly complications that threaten to disrupt things entirely. There are the usual alarming characters, a seductive adventuress, an irascible old gentleman, a sneaky-looking foreigner, and so on. And what is more, all the clues in the mystery seem to be backwards, so that the author's subtitle "A Study in Deduction" is a truism indeed. The very double meaning of the title is not revealed until the last chapter." Buffalo Evening News, - June 23. 1934 "Another Top-Notcher written by Ellery Queen. THOUSANDS of eager fans are awaiting the latest analytico-deductive problem from the author whose books appear in nine different languages, who has never written a failure, and whose most original and exciting thriller is this breathless tale of the unknown man whose body was found in a private room on the 22d floor of a hotel. His death shadowed the lives of seven prominent people, none of whom had ever seen or heard of him. The oddest thing of all was that the victim had his clothes on backward, and that everything in the room where the crime was committed — chairs, tables, even mirrors was turned the wrong way. And why had the mysterious stranger been eating a Chinese orange? Watch how Ellery Queen deducts the astounding solution by treading with infinite patience, through the pulsing tide of terror that sweeps lives and fortunes headlong be fore it." |

|

Published in 1934,

The Chinese Orange Mystery

stands as one of Ellery Queen’s most audacious and baroque

achievements of the classic period, a novel whose reputation among

knowledgeable readers rests less on realism than on its extraordinary

imaginative reach and its radical manipulation of detective-story form. From

its opening pages, the book announces its intention to unsettle

expectations. Inspector Richard Queen is confronted not merely with a

murder, but with a death stripped of identity itself: the victim, found

brutally slain in a private anteroom of the Hotel Chancellor and later

linked to the offices of Mandarin Press, remains unnamed, unrecognized, and

unexplained almost until the final pages. No one connected with the

investigation has ever seen him before; his origin, purpose, and even his

significance must be deduced retrospectively, a reversal of the usual

priorities of the genre. The crime scene compounds this disorientation. Everything is literally backwards. The furniture is reversed, pictures face the wall, the rug is turned upside down, and the corpse itself has been grotesquely manipulated, its clothing worn back to front and ramrods driven up along the spine. This visual perversity is not mere decoration but the governing metaphor of the novel: every clue Ellery Queen encounters seems to point in the wrong direction, demanding that the reader learn to reason in reverse. Contemporary reviewers were quick to recognize the novelty of this approach, calling the book a puzzler even for seasoned devotees of ratiocination and praising its relentless ingenuity (Nassau Daily Review, Jul 10. 1934; Buffalo Evening News, Jun 23. 1934). The New York Times went further, hailing it as “without doubt the best of the Queen stories.” The setting at Mandarin Press, a distinguished publisher of foreign literature run by stamp-collecting magnate Donald Kirk, allows the authors to weave together several of their characteristic obsessions: erudition, collecting mania, and the intersection of high culture with sordid crime. Philately is not a decorative flourish but a motive force, with the murder ultimately tied to the lure of a mythical treaty-port error stamp, a conceit that later drew sardonic comment from philatelist reviewers who admired the authors’ knowledge of stamps more than their prose style (Evening Star, Dec. 15, 1940). Around this core, the Queens assemble a familiar but effective gallery of suspects: an irascible old man, a seductive adventuress, suspicious foreigners, anxious employees, and various subsidiary mysteries that threaten to overwhelm the central problem before Ellery can restore order. |

|

|

Structurally, the novel is both a culmination and an experiment. Like

The Dutch Shoe Mystery,

it relies heavily on architectural space and floor plans, but here the

method is expanded into something almost surreal, a sustained inversion of

normal logic that pushes the puzzle toward the borders of the

impossible-crime tradition. Although no locked room is actually employed,

the book has long been misremembered as one, appearing in polls of classic

impossible-crime novels and being cited by writers as such (Edward D. Hoch,

Mystery Writers of America;

Michael E.Grost).

This collective false memory is revealing: the solution, wild as it may seem

when abstracted, clearly belongs to the lineage of

Chesterton and

anticipates the later, more flamboyant feats of John Dickson Carr.

Indeed, Carr himself explicitly acknowledged the book’s originality in

The Hollow Man (aka The Three

Coffins), noting that Ellery Queen had

demonstrated “still another method…entailing the use of the dead man

himself,” a remark later woven into

Anthony Boucher’s Nine Times Nine as part of

a metafictional discussion of locked-room theory.* Literary allusions further root the novel in its milieu. Dashiell Hammett is mentioned by name, the nurse Diversey may nod toward MacKinlay Kantor’s novel Diversey (1928), and the suspect Macgowan perhaps alludes to Kenneth Macgowan, editor of Sleuths (1931) and author of The Origin of Evil (Michael E.Grost). Such references reinforce the sense that The Chinese Orange Mystery is consciously engaging with the detective genre as a living conversation rather than a fixed formula. Criticism of the book has tended to focus on its uneven pacing and its ending. Some early reviewers felt the solution, once revealed, was disappointingly mechanical, likening Ellery’s deductions to a Rube Goldberg contraption** whose ingenuity threatens to outshine plausibility (Nassau Daily Review, Jul 10. 1934). Others noted sagging narrative energy between the murder and the climax. Yet even these critics conceded the novel’s compulsive pull and its magnetic complexity, qualities that make it difficult to abandon before the final explanation is reached. Seen in retrospect, The Chinese Orange Mystery occupies a crucial place in the Ellery Queen canon. It is not their most realistic novel, nor their most polished stylistically, but it may be their most daring. It fulfills the promise of the early books by pushing deduction into a realm of controlled extravagance, where logic, symbolism, and physical space are inverted to startling effect. For readers steeped in Golden Age conventions, its pleasures lie not only in the solution but in watching the genre itself momentarily turned upside down, only to be triumphantly righted at the end. Movie (more or less): The Mandarin Mystery. |

|

| Evening Star, "Among the stamp collectors"

by James Waldo Fawcett - Dec 15, 1940 "The Chinese Orange Mystery by Ellery Queen is another detective story featuring a murder committed for a postage stamp - a mythical treaty port error. Its author knows something about philately, but not much about the literary use of the English language. His style is a crime more intriguing than that which he attempts to solve." The Courier-Mail, Brisbane - August 25. 1934 - "Some Short Reviews of the Latest Books" "Murder mystery and sudden death are the everyday topics of that clever American writer, 'Ellery Queen,' who shares with his compatriot, S. S. Van Dine (the creator of 'Philo Vance), a wide English popularity. Ellery Queen, visiting the palatial flat of a millionaire friend, discovers a chance visitor not only murdered but the room completely disarranged and the victim's clothes on back to front. The whole setting- of the unusual and peculiar crime has an atmosphere of calculated evil that the author deftly manages to convey to the reader. However, Ellery Queen patiently works his way through half a dozen or so curious little sub-plots, and with characteristic aplomb unearths the real criminal." |

|

Elements for "The Game" There is a challenge for the reader present and in it Ellery apologizes about having nearly forgotten a challenge to the reader in the last book and to have forgotten it in the previous book as well. (There was no challenge in The Siamese Twin Mystery). The story is set during one week in New York where Donald Kirk is beaten to death in the Chancellor hotel. Ellery still wears a lorgnette/pince-nez. A bachelor who has "his own view on marriage". He smokes cigarettes and uses an wooden stick. Richard is close to sixty, uses his snuffbox and wears a cheap wedding ring. Richard studied in Heidelberg, he used to be captain in an outside N.Y. district. He solved a case in 41 St. where cocaine-pusher Dippy Mc Guire got a bullet in the belly. Djuna and Dr. Prouty (with a cigar) reappear. The NYPD is represented by Ritter, Hesse, Pigott, Johnson and sergeant Velie. No mention of the Duesenberg. |

|

| Above: Issue of Redbook from June, 1934 with the complete book-size novel The Chinese Orange Murder. |

|

Notes: * Boucher's exact quote concerning Ellery Queen's Chinese Orange Mystery was: "Ellery Queen has shown us still another method [of tampering with bolts], entailing the use of the dead man himself -- but a bald statement of this, taken out of its context, would sound so wild as to be unfair to that brilliant gentleman." ** A Rube Goldberg contraption is a deliberately exaggeratedly complicated and roundabout way of doing something very simple. The term comes from Rube Goldberg (1883 - 1970), an American cartoonist who became famous for drawings of absurd chain reactions: a ball rolls, taps a lever, which drops a cage, which startles a bird, which knocks over a candle, and so on, all in order to achieve something banal in the end, such as wiping a napkin or turning off a light. In a figurative sense, as in The Chinese Orange Mystery, it means: a solution that is technically correct but constructed so complexly and artificially that it inspires more admiration for ingenuity than for inevitability. In the context of Golden Age detective fiction, this is not an unusual criticism: many readers delight precisely in that baroque complexity, while others experience it as an intellectual contrivance that puts credibility to the test. |

|

The Chinese Orange

Mystery Translations: |

|

Other articles on this book (1) Reading Ellery Queen Jon Mathewson (Feb 2014) (2) The Topsy-Turvy Murder Ho-Ling (May 16. 2013) (3) My Reader's Block Bev Hankins (Jan 13. 2011) |

|

*

Interested readers should know

that the icons/covers

of books, used throughout the

website have extra

descriptions/information not

included in the text on the same

page. Pointing your cursor at

the icon/cover used to reveal

this extra information. To achieve the same effect Firefox users can install an add-on called 'Popup ALT Attribute'. When installed pointing your cursor at an icon/cover results in showing you the details or additional information. |

|

Page first published April 18. 1999 Version 2.0 - Last updated January 17. 2026 |

|

Copyright © MCMXCIX-MMXXVI Ellery Queen, a website on deduction. All rights reserved. |