Columbia University's Butler Library on Thursday, April 28th, [2005,] played host to a 100th birthday bash for Ellery Queen. The Queen stories were collaborations of Frederic Dannay and Manny Lee, a pair of first cousins born in Brooklyn, New York in 1905.

Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, which organized the party and sent out the invitations (though the symposium was open to the public, for free), set a 12:30 start time.

About

sixty people were seated by then

in a small, hot, crowded room,

including

Old-Time

Detection

readers Douglas Greene, Ted

Hertel, Charles Shibuk, and

Steven Steinbock![]() .

.

A

representative from Columbia

greeted the attendees, informed

us of where the special

Ellery

Queen

exhibit was

set up (near the permanent

archives of Dannay's papers and

of Cornell Woolrich's papers),

and introduced the first

speaker, Steven Steinbock![]() .

.

Steve

explained about

Ellery

Queen

the fictional character,

Ellery

Queen

the author,

Ellery

Queen

the anthologist,

Ellery

Queen

the scholar,

Ellery

Queen

the editor... all this while

more people arrived, waving to

and joining those already

seated.

By now

there were seventy attendees,

including young children, some

of them in an overflow room in

the rear.

Above:

Steve Steinbock![]() reminded

us of Columbia's connection to

the Queens. Photo courtesy of

Ted Hertel

reminded

us of Columbia's connection to

the Queens. Photo courtesy of

Ted Hertel

Steve

reminded us of Columbia's

connection to the Queens. The

school back in 1932 invited

Queen to be a guest lecturer --

before it or the world knew that

Queen was two people. That

invitation led to the authors

donning masks to speak, one as

Ellery Queen

and the other as Barnaby Ross

(another pseudonym of the

cousins for a short-lived but

high-quality detective series

featuring a deaf retired actor).

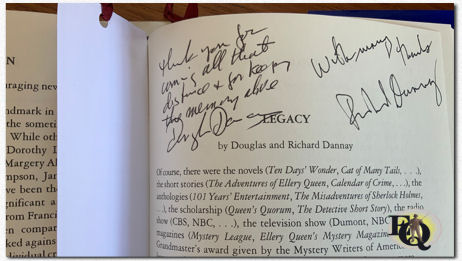

Steve introduced

Richard Dannay, Fred Dannay's

second son, who spoke about

growing up in the household of a

writer and book collector.

"The

postman was a member of our

family, virtually."

Fred

Dannay's library, housed on a

level above the garage, grew so

heavy that the floor buckled.

Fred's two greatest passions,

excluding mysteries, were poetry

and book-collecting. Fred

believed that "poets

are detectives and therefore

detectives are poets."

Indeed, Richard stated: "If

he could have made a living as a

poet, that's what he would have

done."

The two keys to understanding

Fred, he said, are the

Queen-edited anthologies

Poetic Justice

(1967) and

The

Literature of Crime

(1950).

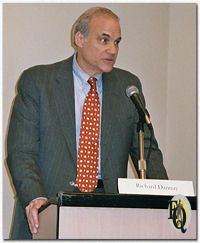

Left:

Richard Dannay

spoke about growing up in the

household

of a writer and book collector.

Photo courtesy of Ted Hertel

Right: Sarah Caldwell spoke

about her grandfather. Photo

courtesy of Ted Hertel

Sarah

Caldwell, the only member of the

Lee family present, spoke about

her grandfather. Manny Lee's

library was housed in a whole

separate cottage on the author's

Roxbury, Connecticut estate.

Manny was a violinist and

collector of 78-rpm record

albums.

Sarah then played a tape recording of her mother, Manny's daughter Patricia Caldwell, speaking from California.

Patricia related a memory from her own mother (the first Mrs. Manny Lee), giving a new slant on how Ellery Queen got his name. The "Ellery" part had long been decided on, named after a boyhood friend of Fred's. But the last name... one night in 1928, during the time they were writing the first EQ book, The Roman Hat Mystery (1929), Fred and Manny were playing cards, probably bridge, when they started looking at the picture cards. Then it hit them. Their brainy sleuth should be christened Ellery King! Before the evening was up, they changed their minds and settled on the Queen.

Patricia drew much laughter when she speculated that the selection of the Queen name may have occurred when the two cousins debated, non-stop over an entire weekend, on whether infinity is finite. (It seems Dannay and Lee found much to disagree on.)

According to the taped Patricia, Manny Lee felt the "most important thing about being a writer is being observant."

Sarah then read a paper from her uncle Rand Lee, a son of Manny Lee. Rand spoke of Manny's love of language. Sarah summed up by saying the cousins' "fiery" relationship probably spurred them to the pursuit of excellence.

Then

came a panel discussion titled "Ellery

Queen:

Sleuth of Many Faces," dealing,

naturally enough, with Ellery

Queen the detective and the

Queen books. The panel comprised

Marc Dolan, Doug Greene, Edward

D. Hoch, Ted Hertel, and

moderator B.J. Rahn.

Panel (L

to R) : Marc Dolan, Ed Hoch,

B.J.Rahn, Doug Greene, and Ted

Hertel. Photo courtesy of Steven

Steinbock![]() .

.

Rahn quickly

outlined the four periods of

Queen to the learned audience,

with reminders of what made each

period unique: Period I,

1929-1935; Period II, 1936-1939;

Period III, 1942-1958; Period

IV, 1963-1971.

Rahn asked the panelists for their favorite Queen books, admitting that she got lost when reading The Greek Coffin Mystery (1932), because of its great number of hypotheses and clues.

In Period I, said Ted Hertel, the point of the books was the puzzle. Hoch said he has read Greek Coffin at least twice but has gone back to re-read its solution many more times.

Nobody disagreed when he said EQ's greatest period was the third.

Period III started with Calamity Town (1942) in which Ellery first goes to Wrightsville. Hertel said he thinks the Queens brought Ellery to the small New England town of Wrightsville, in part, so the authors could rely on Ellery's grey cells instead of the advancing scientific methods of the big cities.

Dolan, who teaches at John Jay College and assigns Queen's Cat of Many Tails (1949) to as many graduate students as possible, says one can make the case that Ellery brings all the troubles to Wrightsville with him. Also the idea that logic is invincible is a trap for Ellery.

Dolan posited that logic no longer was enough. Sure, it solved everything decades earlier for Jacques Futrelle and Carolyn Wells (he quipped, "First time in my life I'm in a room of people who know who Fleming Stone is"); but the strict use of logic could lead to unhappy or thoroughly strange endings such as, he said, the concluding stories of the collections The Curious Mr. Tarrant (1935) by C. Daly King and Clues of the Caribbees (1929) by T.S. Stribling.

Ted Hertel

spoke about the fictitious

J.J.McC, who introduced the

earlier Queen books, and about

the retired Ellery who J.J.

described.

Left: The

ever amiable Ed Hoch! Photo

courtesy of Steven Steinbock![]() .

.

Right: Ted Hertel said

the point

of the books was the puzzle.

Photo courtesy of Steven

Steinbock![]() .

.

Hoch

reasoned that the early Queen

books were introduced by J.J.McC

because the early Philo Vance

stories had been introduced by

S.S. VanD(ine). Hoch then spoke

critically about each of the

Queen short-story collections;

he thinks

The

Adventures of

Ellery

Queen

(1934) and

The New

Adventures of

Ellery

Queen

(1940) are "landmark"

collections; he much prefers

Queen's longer short stories. He

also spoke of Paula Paris,

Ellery's casual date in some of

those short tales. He said the

length requirements of the

various magazines to which the

Queens were submitting might

have proven limiting.

Doug

Greene spoke about the Queens'

radio output -- "The

Adventures of

Ellery

Queen"

ran on radio fairly steadily

from 1939 to 1948. The radio

scripts required much

imagination... every week!

Above:

Doug Greene spoke about the

Queens' radio output

Photo courtesy of Steven

Steinbock![]() .

.

"It's

extraordinary how good so many

of the plays are."

Greene added that "these

two men knew how to promote,"

using the radio show to promote

their books (giving Queen books,

on the air, to guests of the

radio show) and using

Ellery

Queen's

Mystery Magazine

to promote the radio show (by

printing radio scripts in the

magazine).

Hoch proved the point. At the tender age of nine, he bought and read his first adult book, Queen's The Chinese Orange Mystery (1934). He chose it over all others on the drug-store book rack because he had tuned in to the Ellery Queen radio show.

Hertel told how the Queens promoted their first book by writing anonymous letters to editors of newspapers, protesting that Mr. Queen was alerting potential killers to the existence of a new poison.

The panel discussed the cousins' penchant for having the victim turn out to be the villain. "They repeated it so often," said Greene. "Was something driving them to say something? Maybe, anyone who is villainous can also be a victim; anyone who is a victim can also be villainous..."

The final panel, "Queen of All Trades: Editor, Teacher, Critic, Scholar," comprised Lawrence Block, Otto Penzler, Joan Richter, Dorothy Salisbury Davis, and moderator Mike Barr.

Mrs. Davis was the most memorable of the panelists, perhaps because her memories of Ellery Queen went back half a century. She first appeared in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine in 1952.

Now,

having just turned 89 years old,

she had trouble hearing her

fellow panelists, and she

cautioned the audience, "Listen

carefully to what I have to say

to you -- because a lot of it

may not be true."

She's sharp enough not to trust

her memory in its entirety. Her

recollections were a bit

haphazard, disjointed, but

charming. When Davis considered

collaborating with writer Lucy

Freeman, Fred Dannay warned her

on the perils of collaboration.

Above:

Part of the second panel

Lawrence Block, Dorothy Salisbury

Davis, and moderator Mike Barr.

Photo courtesy of Ted Hertel.

Below: Other members of the

panel, next to Mike Barr, (L to

R) Joan Richter and Otto Penzler,

with Sarah Caldwell watching.

Photo courtesy of Kurt Sercu

Davis

visited the Dannay house often,

starting in the 1950s. She

remembered Fred's sons Douglas

and Richard being there. Now,

fifty years later, she gazed

with a slightly puzzled look

into the front row at the Dannay

brothers, now youthful senior

citizens. With perfect comedic

timing and deadpan phrasing, she

addressed the brothers: "You've

changed."

(It brought down the house.)

She remembered forty years ago being with Dannay, John Dickson Carr, Clayton Rawson, Lillian de la Torre, and Ed Radin when they conducted re-enactment experiments in quest of the truth behind the Lizzie Borden case, with Fred Dannay holding a stopwatch and timing certain doings.

Davis believes Fred was cautious in his political comments and highly protective of his magazine. She didn't know Manny Lee nearly as well as she knew Fred Dannay.

Likewise the other panelists. Joan Richter, first published in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine in 1962, met Dannay when she took an adult-ed writing course taught by him when she and Fred both lived in Westchester County (New York State). She and Davis spoke of the pleasure of receiving phone calls from Dannay after he had read their submissions and wished to discuss their stories.

Larry Block, perhaps because he started submitting to Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine in the late 1970s, when Fred Dannay was in his seventies and Manny Lee was already dead, didn't work as closely with Ellery Queen the editor. He just sent his stories in and EQMM published them. "For someone who was so respectful of a writer's work," said Block, "Fred had no respect for a writer's titles," often changing them.

Otto Penzler explained how Queen's Quorum, a Queen-written short-story guide, was influential in transforming him into a mystery collector. Penzler recalled visiting the Dannay house and examining Fred's copy of The French Powder Mystery (1930), in the incredibly rare dust jacket. It's the only first-edition dust jacket of that volume he's ever seen. (When Fred died and the family took inventory, the book had no jacket. That jacket is the holy grail among avid Queen collectors. Nobody has one.)

Penzler spoke of another talent of Queen. "Fred was the first great -- and is still by far the greatest -- anthologist that ever lived. His introductions were so learned and so beautifully written that you had to go on and read the book."

One such introduction appeared in Queen's 101 Years' Entertainment (1941), considered by many scholars the best mystery anthology ever.

Mike Barr, an accomplished writer in comic books, spoke of becoming an Ellery Queen fan in September 1967 (he remembered the exact month!) when he read the first Queen book, The Roman Hat Mystery. He called it "talmudic fiction" wherein every clue means something vital. Those earliest Queen books featured young Ellery making super-complex deductions not unlike the way talmudic scholars in Judaism might mine their holy books for clues and insights.

Barr brought up the topic of paperback original novels that came out (from 1961-1972) under the Queen name but were not written by the Queens and did not have Ellery in them. He believes these were a source of friction between the Queens.

Barr spoke of the 1975/1976 television season when Jim Hutton portrayed Ellery. Barr said he spoke to Hutton at the time, and that Hutton knew the Queen stories and origins but declined Barr's suggestion to phone Fred Dannay for advice or guidance on playing Ellery.

That led someone to ask what involvement Fred Dannay had with the Jim Hutton version of the Ellery Queen show. Richard Dannay summed up his father's involvement: "He watched every episode."

Richard then recalled how, a

half-century ago, he had written

his own Bar-Mitzvah speech. But

then, "a

night or two before the event my

father got hold of it and

completely re-wrote it... I

don't remember if he changed the

title."

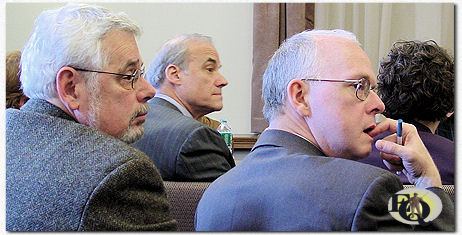

Above:

(L to R) Doug Greene, Richard

Dannay and

Marc Dolan listening intentely.

Photo courtesy of Dale C.

Andrews![]() .

.

The panel

ended, the crowd started to thin

out, people eager to hear more

nevertheless needed to stretch.

But just a half-minute later

began the final portion of the

symposium.

Francis

Nevins, the scholar who has done

the most research into

Ellery

Queen

(and, for that matter, into

Cornell Woolrich), spoke solo to

the audience on "Fatal Fusion:

Uniting Their Separate Talents."

Left:

Mike Nevins![]() spoke solo to the

audience. Photo courtesy of Ted Hertel

spoke solo to the

audience. Photo courtesy of Ted Hertel

Right: Mike in full stride.

Photo courtesy of Kurt Sercu

Nevins![]() focused on the process of

collaboration between the

Queens. With just a few

exceptions -- for instance,

Nevins said the excellent short

story "The Dauphin's Doll" is

the only Queen tale completely

written and plotted by Manny Lee

alone -- each of the Queen works

was the product of both Dannay

and Lee, and to try to remove

either from the equation would

leave us with no body of

Ellery

Queen

work worth

commemorating.

focused on the process of

collaboration between the

Queens. With just a few

exceptions -- for instance,

Nevins said the excellent short

story "The Dauphin's Doll" is

the only Queen tale completely

written and plotted by Manny Lee

alone -- each of the Queen works

was the product of both Dannay

and Lee, and to try to remove

either from the equation would

leave us with no body of

Ellery

Queen

work worth

commemorating.

Their process was simple in theory though difficult to execute: "They collaborated by combat."

The Queens tried every possible way to collaborate and eventually -- we don't know just when, but almost certainly by 1940 -- found their preferred method: Fred Dannay would create extremely detailed, plot-rich outlines explaining the clues, characters, events, motives, some of the dialogue -- all told, accounting for (from various estimates) perhaps 25% of the wordage of the finished novel; Manny Lee would execute the outline, put meat on the bones, work out each incident, provide the descriptive prose, and add the bulk of the dialogue. Which is not to say that the lines separating what one Queen did from what the other Queen did were never blurred or crossed. There could be a lot of give and take, or a lot of disagreement.

Nevins has read the Dannay-Lee correspondence (housed at Columbia) and the Manny Lee-Anthony Boucher correspondence (housed at Indiana University) to learn as much as he could about the cousins' workings.

Nevins believes a key to understanding Fred Dannay is The Golden Summer (1953), written under Fred's birth name of Daniel Nathan. Nevins calls this an auto-biographical novel, with its main character, little Danny Nathan, master manipulator and scheming entrepreneur, showing many of the traits of the brilliant early Ellery Queen.

The Queens' partnership was not always harmonious. Letters in the separate archives show the duo had numerous disagreements, emotionally charged and long-lasting. "What most people would shrug off as water off a duck," said Nevins, "these two would take as mortal insults."

Nevins read aloud some of the Queens' more vitriolic letters to each other. The authors' true views toward each other, he speculated, we'll probably never know; he said the only comparison he could think of for such a combative partnership is that of the George and Martha lead characters in Edward Albee's play Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

"Isn't it amazing," he summed up, "that these guys could collaborate for forty years?"

Yet collaborate they did. So much so that today, 77 years after they began their Queenly work at the age of 23, we honor their memory, their talent, their legacy.

In the words of Nevins, these two very human cousins, Fred Dannay and Manny Lee, "created magic for forty years, and most of that magic can be reduced to two words -- Ellery Queen."