|

![]()

|

JAPANESE SCHOLARSHIP: LOGIC, FORMALISM, AND ELLERY QUEEN

This particular rabbit hole is called “the Late Queen Problem” (kōki kuīn-teki mondai in Japanese). It’s a term I came across several times in my research but was confounded by what it meant. I searched for explanations, first in English and then in Japanese, but nothing was terribly clear or helpful. I found a Reddit page about computer games in which someone asked the same question. One responder said, “I believe it's a Japanese-only theory.” I decided to find out what it was, and why Japanese mystery fans were talking about it.

“The Late

Queen Problem” is a lively debate among Japanese mystery

fans and writers which examines the works of EQ through the

lens of early Twentieth century theories of logic and

literature, ultimately asking the question of

whether or not true “fair play” can exist on detective

stories. |

|

|

|

|

|

Definitions and Caveats The phrase “Late Queen Problem” is itself problematic. As I said above, the debate was triggered by the 1995 essay “Early Queen Theory” (shoki kuīn ron) by mystery novelist and critic Norizuki Rintarō, published in the Japanese journal Contemporary Thought. It focused primarily on the novels The Greek Coffin Mystery, The Tragedy of Y, and The Siamese Twins Mystery, all written by Dannay and Lee, in the years 1932 and 1933. “It is still unclear where the term “Late Queen Problem” originated,” wrote MORŌKA Takuma in his book-length A Study of Honkaku Mystery: On the Late Queen Problem. “But the term is believed to have first been used by KASAI Kiyoshi in his article, ‘The Third Wave of Honkaku Detective Fiction’ in 1996, in which Kasai referred to Norizuki’s theory as a ‘Late Queen-like Problem.’ Kasai’s article focused on Ten Days of Wonder (1948), a late Queen novel . . .” The terms “Problem” and “Theory” in these titles are also confusing. In English, problem generally signifies a difficulty or challenge. If so, what’s the problem? While some have argued that Norizuki’s article proved that fair play in detective fiction is impossible, that view is far from universal. The word mondai (問題) can refer to a question (such as in a quiz), a societal or political issue, a controversy, or a difficulty. But it may also refer to a discussion or debate. Similarly, ron (論) is usually translated as “theory,” but can also mean “dispute,” “discourse,” or “treatise.” In my view, the “Late Queen Problem” may contain some controversial ideas, but it doesn’t constitute a “problem” per se, and while Norizuki’s essay offers a variety of fresh ideas and theories, it doesn’t constitute a unified group of propositions in the same sense that we use the term in English (such as in “Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity”). Nevertheless, for this article we’ll stick with the translations “Early Queen Theory” for Norizuki’s initial article, and “Late Queen Problem” for the wider response it generated. Another problematic term is Honkaku, a concept which is central to this discussion but doesn’t easily translate into English. Honkaku is understood as meaning “authentic” or “traditional,” but as used by Norizuki and others in the context of the “Late Queen Problem,” Honkaku specifically refers to detective fiction that adheres to the rules of fair play (in which the author provides all the relevant clues needed to solve the mystery before the detective reveals the solution). The figure of “Ellery Queen” presents an interesting problem that, as we’ll see, is very relevant to this discussion. “Ellery Queen” was the pen name used by Frederic Dannay and Manfred Lee from 1929 to 1971. But prior to 1936, their identity was unknown to the public. The author of the novels was only known as “Ellery Queen,” which is also the name of the hero-detective character in the Queen books. Since this article only concerns books written prior to 1936, I will generally refer to the author of the Queen books as “Ellery Queen” or simply as “Queen” (rather than “Dannay and Lee”). The fictional detective-hero Ellery, son of Inspector Richard Queen, will be referred to as “Ellery” or occasionally, in the Japanese fashion, as “Detective Ellery.”

A few important caveats: Norizuki and others have taken some liberty in applying philosophical principles to the works of Queen. Specifically, Norizuki uses Russell’s “Type Theory,” Gödel’s “Incompleteness Theorems,” and the concept of metalanguage. Much of this is based on the work of Kojin Karatani as well as from Douglas R. Hofstadter’s Gödel, Escher, Bach. Whether or not these theories were intended to analyze detective fiction, I leave up to the reader. I’m not versed enough in theoretical math or logic to pass judgement, but I found the ideas compelling, and they’ve enriched my appreciation of the works of Ellery Queen. Several of the interpretations question the very idea of Fair Play. I take this with a grain of salt, particularly because several of those who have made such claims have gone on to successful careers writing detective stories based on Fair Play plotting. Rather than marking the death of traditional crime stories, the “Late Queen Problem” seems to have triggered a renaissance with various writers experimenting with and expanding on the plot-devices of Queen. |

|

|

Norizuki Rintarō’s Early Queen Theory The Late Queen Problem began with Norizuki’s 1995 article “Early Queen Theory.” Mor ōka Takuma, quoted above, called it “the epicenter of an earthquake” which inspired a new wave in Honkaku detective fiction. Because of its significance, it’s worthwhile to look at a short outline of Norizuki’s main points (based on the revised version of the article which Norizuki included in his 2007 collection of critical essays, The Complex Art of Murder):Introduction: Norizuki discusses Japanese philosopher/literary critic Kojin KARATANI, who in the 1980s was fixated with the “Gödel Problem” (Kurt Gödel’s “Incompleteness Theorems”) and its application beyond the realm of mathematics Part 1: Formalization and Van Dine. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, “Formalism” was a common catchword in intellectual circles. The label “Formalism” was applied to diverse fields including logic, art, mathematics, linguistics, anthropology, and literature. Norizuki points out that American art and literary critic Willard Huntington Wright (S.S. Van Dine) was in the middle of this avant-garde intellectual world. Wright enjoyed detective fiction, but believed the genre was held down by its romanticism and sensationalism. In The Great Detective Stories (as Wright) and in his Philo Vance novels and his “Twenty Rules for Writing Detective Stories” (as Van Dine), he set out a manifesto for the Formalization of detective fiction.

Part 2: Ellery Queen and

Formalism.

Part 3: Metafiction: Queen as Author and Detective. In the early books of Ellery Queen, Dannay and Lee developed several innovations. The first was the use of the name “Ellery Queen” as both the author of the novels and the detective within those novels. This same “Ellery Queen” also served as third-person narrator. The second innovation was the use of a “Challenge to the Reader” in which (in eight of the first ten novels) (4). Ellery himself, as both novelist and detective, addressed the readers directly and pronounced that all the evidence necessary to solve the mystery had been presented. By doing this, Queen wasn’t merely breaking the “fourth-wall,” he was also transcending – or transgressing – addressing the reader meta-fictionally in order to avoid logical paradoxes. (More on this below). Part 4: The Greek Coffin, Infinite-Meta-Laddering, and the Gödel Problem. In the 1932 novel The Greek Coffin Mystery, the fourth book in the series, Ellery Queen not only tests the boundaries of Logical Type Theory, but also demonstrates Kurt Gödel’s “Incompleteness Theorems” (which show that in a by showing that within a closed axiomatic system, the truth is ultimately unprovable). In The Greek Coffin Mystery, borrowing a page from E.C. Bentley’s 1913 novel Trent’s Last Case, with all the evidence available to him at each point, Ellery comes to several incorrect solutions before reaching the “correct” solution. Queen further tests logic with The Tragedy of Y and The Siamese Twin Mystery. In this section, Norizuki also discusses the “faceless-corpse” plot device used in several early Queen novels. Norizuki’s article shook the Japanese mystery world. Debates, discussions, and disputations occurred on university campuses, in coffee shops, and online. A year later, Kasai Kiyoshi addressed the issue and suggested that this “Late Queen Problem” marked the beginning of the “Third Wave of Honkaku Detective Fiction.” In the sections below I’ll touch on several of the main points of the theory with examples from the Queen canon and other source s. |

|

|

Form-Fitting Fiction During the late-Nineteenth and early-Twentieth centuries, Formalism was a popular intellectual trend that spanned science and the arts. The term Formalism was applied to the math of Frege, Hilbert, Whitehead, and Russell. Boris Tomashevsky was at the center of a school of literary criticism called Russian Formalism. Leonard B. Meyer applied it to the study of Brahms, Beethoven, and Stravinsky. Sergei Eisenstein and others espoused Formalist Film Theory. Similar movements developed in painting, law, linguistics, and anthropology. None of these movements were directly connected, but what they shared, aside from the word “Formal” and the general zeitgeist, was the goal of limiting external elements such as interpretations and context, and identifying the formal relations and structures. Formalism involves constructing an artificial, autonomous world – a “system” – and putting all labels and terms into brackets in order to determine rules and relationships within that world. Computer algorithms and board games are both formal systems, as are the shapes and colors on a painting by Kandinsky or Mondrian. Likewise, within the confines of its pages, a novel can be understood as a formal system.Willard Huntington Wright (who also wrote as S.S. Van Dine) was the first to formalize detective stories. An art critic immersed in the avant-garde world, Wright described detective fiction as “a complicated and extended puzzle cast in fictional form.” He went on to say that detective fiction “has set up its own standards, drawn up its own rules, adhered to its own heritages, advanced along its own narrow-gauge track, and created its own form and technic.” Using the pen name S.S. Van Dine, Wright authored twelve novels featuring dilettante detective Philo Vance. He also proposed a list of the “Twenty Rules of Detective Novels” that emphasized the emotionless tradition of the Russian Formalism and at the same time affirmed the core values of Fair Play detective fiction. As Norizuki Rintar ō put it, “when advocating the ‘Principle of Fair Play,’ Van Dine had in mind the honkaku detective novel.” |

|

|

The Barber Paradox Mystery and the Invention of Queen When Dannay and Lee set out to create

their own detective, they drew on Van Dine’s popular “Philo

Vance” series, and ultimately improved on the model. “He

influenced us because he made so much money,” Dannay once

admitted, but added, “the kind of thing he did appealed to

us in those days. It was complex, logical, deductive, almost

entirely intellectual.” Biographer

Francis

M.

Nevins

S.S. Van Dine puts a twist in his storytelling by having the adventures of Philo Vance narrated by Philo Vance’s friend, coincidentally named “S.S. Van Dine.” By using his own pen name as the identity of the first-person narrator, Van Dine was free to interact with the reader, providing observations and frequent footnotes, from within the novel. Dannay and Lee took this a few steps further. They used their pen name – “Ellery Queen” – for their hero detective as well as the third-person narrator of the novels. A close reading of the books’ forewords (by a fictional J.J. McC) and in the “Challenge to the Reader” makes this fact clear. The following, for example, is from the “Challenge” in The Dutch Shoe Mystery (emphasis added): "... Remember that knowledge of the article which the author extracted from the cabinet in the Anteroom, and of the information which the author gave to Harper over the telephone in the preceding chapter is not necessary to the solution . . . although if you have correctly followed the logic you may deduce what the article was and, with less certainty, what the information was. To avoid any charge of unfairness I submit the following refutation: that I myself deduced the answer before going to the cabinet and before telephoning Harper. Ellery Queen" Whether this was conscious on the part of

the two cousins is uncertain. But it had important

consequences on the logic of their novels. To understand the

significance, we have to move to the realm of formal logic.

In 1901, British philosopher and logician Bertrand Russell

discovered the following logical paradox:

Translated into English, it means something like: “The set of all sets can only be a member of itself if it is not a member of itself.” A popular analogy is the “Barber Paradox”: In a town there is a single barber who shaves all and only those who do not shave themselves. Who shaves the barber? Assuming the barber is shaved, he’s in the paradoxical situation of having to shave himself, while not being able to shave himself according to the rules. Russell offered a solution to his paradox called “Type Theory” which eliminates the vicious circles of paradox by requiring that sets be ordered into a hierarchy of types. Using the analogy of the Barber Paradox, the barber is of a different “type.” He exists on a different hierarchical level than the rest of the townspeople, so the rule “who shaves all and only those who do not shave themselves” doesn’t apply to him. A detective story is like the village in the Barber Paradox. The narrator of a detective story exists on a higher level than the characters within the story. The author and reader of the story exist on an even higher level. When a character from one hierarchical level trespasses into another, paradox occurs. Norizuki refers to these intrusions as “Logical Type Confusion” or “Logical Type Transgression.” In Golden Age detective fiction, the most famous “Type transgression” occurs in a particular novel by Agatha Christie in which the narrator turns out to be the killer. (I don’t need to name the novel. If you don’t know what I’m referring to then you haven’t read enough Christie). (As an interesting sidenote, Van Dine and Queen had different opinions about that particular Christie novel. Van Dine called the plot “hardly a legitimate device of the detective-story writer” and in his “Twenty Rules” referred to it as “bald trickery, on par with offering some one a bright penny for a five-dollar gold piece. It’s false pretenses.” Queen, on the other hand, reviewing this book in the first issue of Mystery League, said that the book was “Just short of excellent. Deserves classic rating on basis of its surprise solution.” Regarding the fair play of the book, Queen gave it a score of 10 out of 10.) |

|

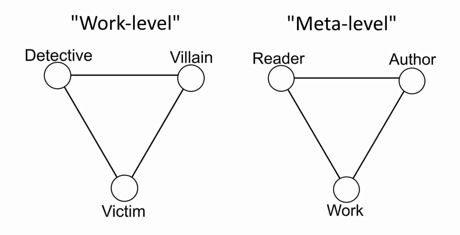

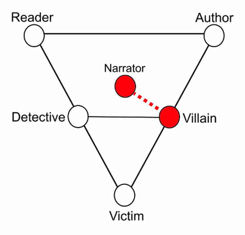

| Norizuki’s 1999 article “On the Masterpieces of 1932” served as a follow-up to his own “Early Queen Theory” and a response to Kasai Kiyoshi. Following Kasai’s model, Norizuki illustrated the formalism of detective stories using a series of inverted triangles. In the diagram below, the first triangle represents the “Work” – the detective story itself. In it, we see the Detective and Villain opposed to each other at the top, with the Victim (also represented as Corpse or Crime) at the fulcrum of the triangle. | |

|

|

|

The second triangle represents the relationship between the Author and Reader, and the Work itself. Norizuki calls this the Meta-level since it exists outside of the story. In a Fair Play detective story – particularly one such as the early Queen books in which the Author explicitly challenges the Reader to solve the mystery before it is revealed, Author and Reader are seen as in opposition to each other, both trying to solve the mystery (i.e. the Work, or Corpus if we want to draw parallel to the Corpse).The

Work can be seen nested within

the Meta-level: Note that on the left side of the triangle, both the Reader (outside of the work) and Detective (within the work) are engaged in the parallel tasks of solving the mystery. On the right side of the triangle, as though on the opposite side of the chessboard, Author and Villain are in opposition to Reader and Detective respectively. |

|

|

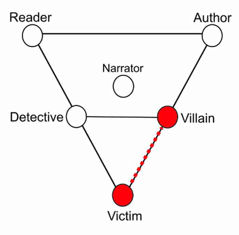

When a character trespasses from one hierarchical level to another, Norizuki calls it “logical Type confusion” or “logical Type transgression.” We’ve already seen an example of this in Queen’s work when the Author and Detective, as well as the Narrator, are all the same person. Kasai seems to suggest that in honkaku – or fair play – detective stories, Russell’s Type Theory needs to be observed. Violation of logical Type invalidates the pretense of fair play. |

|

|

Note that Kasai’s orthodox approach to paradox is similar to Van Dine’s regarding that certain Agatha Christie novel. Norizuki’s more embracing attitude toward Type transgressions is more like Ellery Queen’s recognition that the Christie novel was not a violation of fair play . |

|

|

There are a variety of logical Type transgressions in classical detective fiction. I previously mentioned a controversial Agatha Christie novel in which the confusion of logical Type took the form of Narrator=Villain.  |

|

During the years 1932 through 1933, Dannay and Lee

experimented with a different, and utterly brilliant trick

using logical Type confusion. Of the eight novels written

during those years, five include some variation of

Villain=Victim. These took

various forms, some involving the “faceless corpse” device,

or what Nevins calls “the Birlstone Gambit” (based on an

incident in Conan Doyle’s Valley of

Fear). In some cases, it appears that a corpse is

responsible for murder. In one particular book a corpse

orchestrated a murder before his own death. |

|

|

Gödel and the Greek Coffin 1932 and 1933 were the most prolific in the career of Manfred Lee and Frederic Dannay. During those two years, eight novels by the cousins were published, four under the name “Barnaby Ross” and four under the name “Ellery Queen.” It also happened to be during this period that they created some of their cleverest plots. The Greek Coffin Mystery was the first book published in 1932, and the fourth novel in the “Ellery Queen” series. With a plot reminiscent of E.C. Bentley’s Trent’s Last Case (1913), Ellery proposes several incorrect solutions based on a series of false clues, resulting in what Norizuki describes as a “Gödel Problem” based on Karatani’s interpretation of Kurt Gödel’s “Incompleteness Theorems.” It is also with Greek Coffin that we begin to see the character of Ellery grow into something more human, and certainly more humble, than the Philo Vance clone he started out as. I have to say, though, that in my opinion, The Greek Coffin Mystery is not the most readable of the early Queen novels. The writing is not Queen’s strongest, and many of the characters are shallowly drawn. Some of the depictions, although a product of their time, will be painful for modern readers. These flaws, however, are cosmetic. On to the story. The Greek Coffin Mystery opens with mourners preparing for the burial of Georg Khalkis, a New York art dealer who has died of natural causes. Immediately following the funeral it’s discovered that Khalkis’ Last Will and Testament is missing from the wall safe where it was seen just prior to the burial. After every person at the Khalkis home or attending the funeral is searched, and every avenue by which the will could have been disposed is investigated, Detective Ellery concludes that the only place the will could have been secreted was inside the coffin of Georg Khalkis. The coffin is disinterred, but everyone, especially Ellery, is surprised to find that the will is not inside the coffin. What they do find is a second body, that of convicted art thief and forger Albert Grimshaw. Midway through the book Ellery comes up with the solution based on all the evidence and testimonies presented up to that point. It’s a shocking solution and a brilliant example of a logical Type transgression. But shortly after the denouement, new testimony is provided that disproves Ellery’s solution. After the embarrassment of his incorrect solution, Ellery discovers several new pieces of evidence leading to a second solution to Grimshaw’s murder. Ellery identifies Suspect #2 as the true killer and the author of the false clues that led him to his previous wrong solution. But over the next week, Ellery begins to harbor doubts. By the time Ellery announces a third solution, the case has taken on international proportions. But once again, shortly before the “Challenge to the Reader,” Ellery reveals that Suspect #3 is innocent. As the novel concludes, Ellery manages to entrap the true criminal who had been planting false clues along the way. Each of the wrong solutions were based on false clues created by others (5). In this sense, each of the embedded triangles in the chart represents a completed mystery, authored, it seems, by the next suspect. The idea of a character authoring a mystery within a mystery is made even more painfully explicit in The Tragedy of Y, published later that year.

|

|

|

Norizuki refers to the structure of Greek Coffin as an “infinite meta-ladder,” suggesting the possibility that after a series of incorrect solutions, what if the fourth solution is also incorrect. In his book Ellery Queen Theory, Iiki Yusan points out that The Greek Coffin Mystery is ostensibly (and explicitly stated in the actual book’s foreword) Ellery’s own memoir of a case early in his career. What if, a year or two after the publication of the book, new evidence was to surface proving the innocence of Suspect #4 and that a fifth suspect set the entire thing up? We know, of course, that Greek Coffin is a work of fiction, and that the entire story is contained within its covers. But for Norizuki, Kasai, and others, the story suggests an interesting application of Gödel’s “Incompleteness Theorems.” Hofstadter (Gödel, Escher, Bach pg. 17) paraphrases Gödel’s theorem: “All consistent axiomatic formulations of number theory include undecidable propositions.” It was Kojin Karatani, beginning in 1983, who suggested that Gödel’s Theorems have applications beyond mathematics. Much of the debates and discussions of the “Late Queen Problem” seem to focus on Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems to the point that many seem to equate the two. I find this a little troublesome, first, because this mathematical square peg wasn’t intended to be forced into the round hole of literature (6), and second, because it overshadows so many other fascinating aspects of Norizuki’s “Early Queen Theory” and “On the Masterpieces of 1932”as well as the entire debate called the “Late Queen Problem.” A story is complete when the author finishes it. Loose threads and plot-holes aside, I’m skeptical of the idea that a detective story is incomplete because of the possibility that the fictional detective missed a clue. Even when a story is based on a true crime, such as Poe’s “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt,” the story is a complete work in itself despite actual clues from the Mary Rogers murder case that Poe did not include in his story. The most compelling features of the “Late Queen Problem” for me are the ways Norizuki and others explored the logic of detective fiction, and the use of Russell’s Type Theory to map the participants of a story – both within the text and outside the text – in order to understand the paradoxical plot-twists that made Queen such an important mystery writer.I learned a lot during the six months I spent at the bottom of the “Queen Problem” rabbit hole. It has expanded my understanding of the Japanese idea of honkaku mysteries and has deepened my appreciation of Ellery Queen. Early in my research, I felt I needed to take a closer look at Queen. So over a period of a few months, I sequentially reread the first fourteen Queen novels (7) and was enriched by that experience. If I had more time and space, I’d further explore the ramifications of the “Late Queen Problem” on interpreting The Egyptian Cross Mystery, The Siamese Twin Mystery, and The Tragedy of Y. There is much more to say, but for now I beg your pardon as I remain humbly yours, incomplete . |

|

|

ENDNOTES 1. Japanese names are tricky for Westerners due to the fact that it’s been our custom to reverse the order of their names. Throughout this article, I’ll attempt to refer to Japanese writers by their Japanese names, with their family-name first and their given-names after rather than swapping their names Western style. For those writers that have been widely published in the West and are known by their Western-ordered names, I’ll follow the Western custom. At the first mention of any Japanese names, I’ll follow the convention recommended by the Japanese government of typing their family name in upper-case letters. Thus, Norizuki Rintarō (whose family name is “Norizuki”) it will first appear as NORIZUKI Rintarō, and Kojin Karatani (whose family name is “Karatani”) will appear as Kojin KARATANI. In subsequent mentions, I’ll normally refer to them by their family name only, and only capitalize the initial letter of their name. 2. Mr. Iiki’s name is itself a clever bit of wordplay: spelled out phonetically in Roman characters, his name (IIKI YUSAN) can be rendered ii kyuu san, or EQ3 (san being the word for “three”). Before adopting this penname, he was known as EQIII. 3. I’m grateful to Mr. Iiki for his help, and for providing me with copies of many of his Queen related works, including Ellery Queen: The Complete Guide (エラリー・クイーン完全ガイド, 2021), The Knights of Ellery Queen (エラリー・クイーンの騎士たち―横溝正史から新本格作家まで, 2013), Ellery Queen Theory (エラ リー・クイーン論, 2010), and Absorbed in Honkaku Mysteries (本格ミステリ戯作三昧, 2017). The English titles I’ve provided for these books are close approximations. Translating form Japanese to English and vice versa is a complicated process. Literal translations of these titles, or in some cases, the English versions of the titles provided by the author, will be ambiguous and likely to convey the wrong meaning. 4. In the first Queen novel, The Roman Hat Mystery, the “challenge” is delivered by Ellery’s fictional friend and unofficial editor J.J. McC. The seventh novel, The Siamese Twin Mystery, for various reasons does not include a “challenge.” 5. To be fair, Ellery himself was the author of the false clues that led to one of the incorrect solutions. I can’t say which. 6. Again, to be fair, Norizuki wasn’t directly applying Gödel to Queen’s stories. He was applying Kojin Karatani’s broad interpretations of Gödel’s theorems to Queen. 7. Full disclosure: I read the twelve Queen books from The Roman Hat Mystery through The Devil to Pay, and only the first two “Drury Lane” novels written under the Barnaby Ross pen name. I used the word “reread” but I believe this was my first reading of five or six of the books. |

|

|

|

|

|

Other articles by this West 87nd

Street Irregular

Page first published on August 9. 2022

|

|

|

|

|

| Introduction | Floor Plan | Q.B.I. |

List of Suspects | Whodunit? | Q.E.D. | Kill as directed | New | Copyright Copyright © MCMXCIX-MMXXV Ellery Queen, a website on deduction. All rights reserved. |